I am a mish-mash of two people whose deaths started with losing their minds. And while I have no idea how I’ll go, I’ve always suspected it’s too much to ask for some clean, sane break.

What I’ve learned is that there is maybe one thing you can keep, in madness, if you devote your all to holding it tightly.

My mom kept her sense of humor. Even in the days before the end, when her limbs didn’t obey and she didn’t open her eyes and her murmurings were not for us, she’d laugh now and then. Sometimes even in response to us, out here.

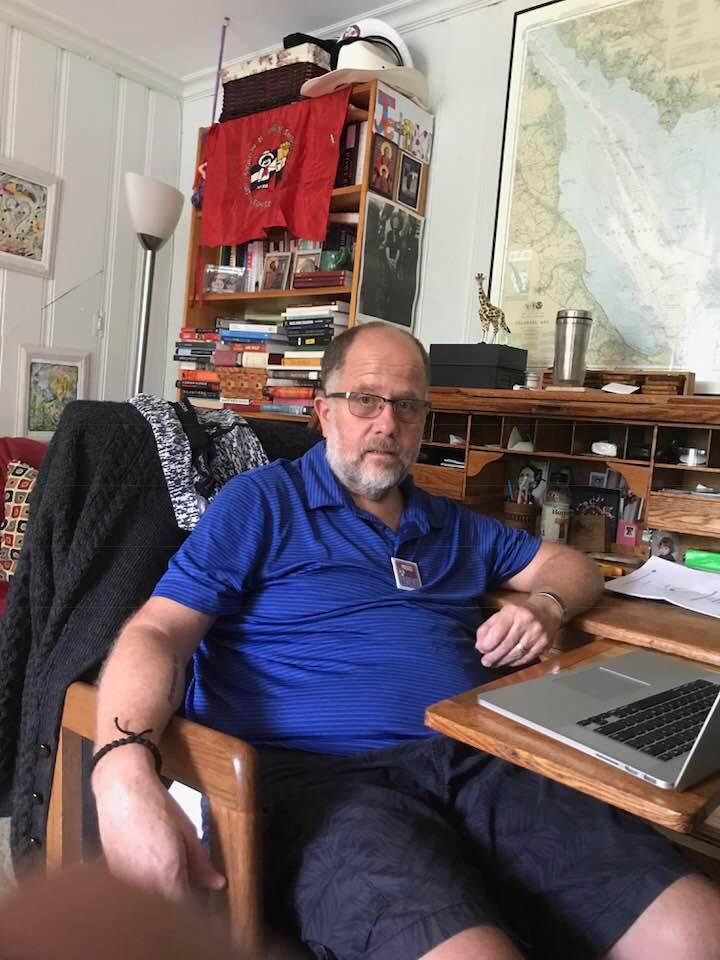

My dad kept the tidbits.

This is hard to explain. My dad loved jeopardy and always had the answer before those on the show. Ok, so maybe it’s easy to explain. He kept the tidbits.

It seems hard to hold. Maybe it was. It was certainly the source of an odd discomfort, in the days following his death. He hadn’t held onto his place, his reality. Hadn’t been able to keep up with the sporadic shuffling of his earthly form between my stepmother’s home, an expensive home with a three story entry that kept him and other “memory care” residents in an odd basement hallway that smelled like shit, my stepmother’s home again, but devoid of his things, and then the state home he was shoved quickly into for his final days.

He remembered the odd facts, though. He’d break out sometimes with some random story about birds. A litany of quiet rage about the treatment of prisoners, homeless folks, and others we call “crazy.” He remembered the purpose of the prayer beads around his wrist.

The day after his death, we gathered at my stepmother’s house by default. She declared pointedly that she wanted to focus now on forgetting all of what he was when he was sick, and I was quiet for that. My cousin shared a story, though, about how he had remembered a story about monks hiking together or some shit, and had marveled that he had remembered that, but not where the bathroom was.

“It seems like you can keep one thing, if you focus hard enough,” I said, then.

They were quiet about that. A silent wave of different reactions, different feelings washing over their faces, ranging from indignation to adoration, all based over with grief.

I will not forget how my father was, sick. He was himself then, too. He was himself, and it took effort, and it is so, so rare that we die as ourselves. Especially with dementia.

I hope that’s what they say about me. No matter how my survivors feel of themselves in my story, I hope at least one of them feels they can say that I died as myself.

Leave a comment